“The essence of deception is to mask the truth so well that even the vigilant are led astray.”

— Anonymous

Currently, there is much (appropriate) applause for actions taken regarding the removal of petroleum-based dyes from our current supply of ultraprocessed foods (UPFs). However, from an industrial reformulation perspective, in the grand scheme of things, this is a pretty small give on the part of industrial food manufacturers. Beyond the window dressing of dyes to make foods more visually appealing, within UPFs, there are engineered compounds that are often marketed for presumed health benefits.

These include sweeteners or sugar substitutes, such as aspartame, sucralose, stevia-derived substances, and xylitol (covered in a previous column here). The alleged health benefits associated with using these sweeteners instead of traditional sugar (sucrose) include caloric reduction, minimal blood glucose effect, and the lack of adverse side effects or complications. As noted by the US Food and Drug Administration, “Under the law, certain ingredients do not require pre-market food additive approval by FDA, for example, if they are generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by qualified experts. If a company concludes that the specific use of a sweetener is GRAS, they may submit their information to the FDA through the FDA’s GRAS Notification Program.”[1] It is estimated that over 10,000 food additives have achieved approval through this pathway. And like a bloodsucking tick, once embedded into the modern food system, they can be difficult to remove.

This includes artificial sweeteners like aspartame, which is the primary sweetener found in diet soft drinks like Diet Coke. As far back as 2021, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) found concerns with this sweetener in particular. In 2023, IARC again raised concerns that aspartame was “possibly carcinogenic to humans.” As recently as 2025, the US Food and Drug Administration’s response was to “disagree with IARC’s conclusion that aspartame is actually linked to cancer.”

Now, a recent study provides novel insight into how the artificial sweetener aspartame increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), strengthening the epidemiological observation that humans consuming diet beverages containing aspartame have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, e.g., heart attack, despite the aforementioned negligible caloric content or blood glucose effect.

- The study used both a mouse and a primate model.

- The animals consumed a diet containing 0.15% aspartame over 12 weeks, the equivalent of approximately three 12-ounce Diet Cokes per day.

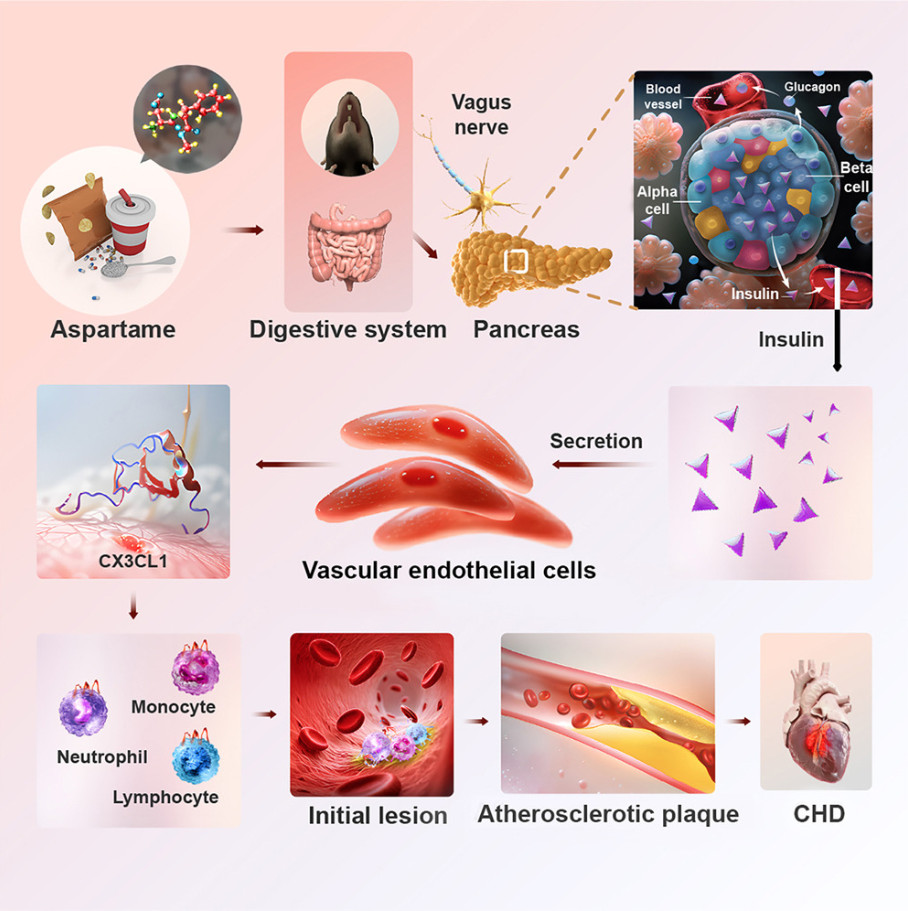

- Within the gastrointestinal tract, aspartame initiated its effects through the activation of the vagus nerve, followed by a rise in blood insulin levels.

- Subsequent insulin-dependent mechanisms exacerbated the development of atherosclerosis, associated with coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction.

- Preventing parasympathetic nervous system activation and/or blocking specific immune cell functions (production of the CX3CL1 chemokine) inhibited atherosclerosis formation.

Proposed mechanism of aspartame involvement in Coronary Heart Disease (atherosclerosis). Reproduced from Wu et.al. (2025).

The Caveat:

Like all animal studies, care must be taken to extrapolate the results to humans. Nonetheless, the findings and mechanisms elucidated in this particular study correlate with decades worth of research linking the consumption of non-nutritive sweetened (NNSs) comestibles like Diet Coke to a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

In a manner much like type II diabetes, the consumption of the artificial sweetener aspartame in this study caused a rise in insulin levels and higher levels of inflammation, which over time was associated with the development of atherosclerosis. A process that in humans leads to an increased risk of heart attacks and stroke over time. It was also interesting that aspartame, at 200 times the sweetness of sucrose, seemed to elicit a more robust release of insulin than the sugar it was intended to replace, despite adding essentially zero calories.

According to the FDA, the maximal recommended daily intake of APM is 40 mg/kg bodyweight in Europe and 50 mg/kg bodyweight in the United States. Unfortunately, NNSs are so ubiquitous in ultraprocessed foods, the mainstay of the average American’s diet, that adults and children often exceed those levels. Excess consumption has been associated with various diseases, including obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cancer, cardiovascular disease (CVD), allergies, neurological disorders, and behavioral disorders.

While the current initiatives are necessary and laudable, we must be vigilant against being satisfied with superficial substitution. Ultraprocessed foods are not the innate endpoint of consuming natural foods, like drying jerky or fermenting wine; they are wholly another thing, one that cannot be undone with simple reformulation.

[1] (USFDA, 2025)

The Study:

Additional resources:

Czarnecka, K., Pilarz, A., Rogut, A., Maj, P., Szymańska, J., Olejnik, Ł., & Szymański, P. (2021). Aspartame—True or False? Narrative Review of Safety Analysis of General Use in Products. Nutrients, 13(6), 1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061957

Leasca, Stacey. More Than 10,000 Chemical Food Additives Ended Up in the U.S. Food System — Here’s Why. Food & Wine. 2024. https://www.foodandwine.com/fda-food-additives-gras-designation-loophole-8761817?

Oyama, Y., Sakai, H., Arata, T. et al. Cytotoxic effects of methanol, formaldehyde, and formate on dissociated rat thymocytes: A possibility of aspartame toxicity. Cell Biol Toxicol 18, 43–50 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014419229301US Food and Drug Administration. Aspartame and other sweeteners in food. February 27, 2025.