“I want there to be no peasant in my realm so poor that he will not have a chicken in his pot every Sunday.”

— Attributed to King Henry IV of France (late 16th Century)

For the last half-century, dietary and health experts in the United States have echoed the same mantra, albeit for different reasons. According to their logic, which remains the dominant advocacy, avoiding red meat and consuming leaner options like chicken leads to improved health outcomes. But the modern incarnation of King Henry’s yard bird is a far cry from its free-ranging ancestor. And, like so many trends originating in the 70s (polyester suits and disco, anyone?), these recommendations have failed the test of time.

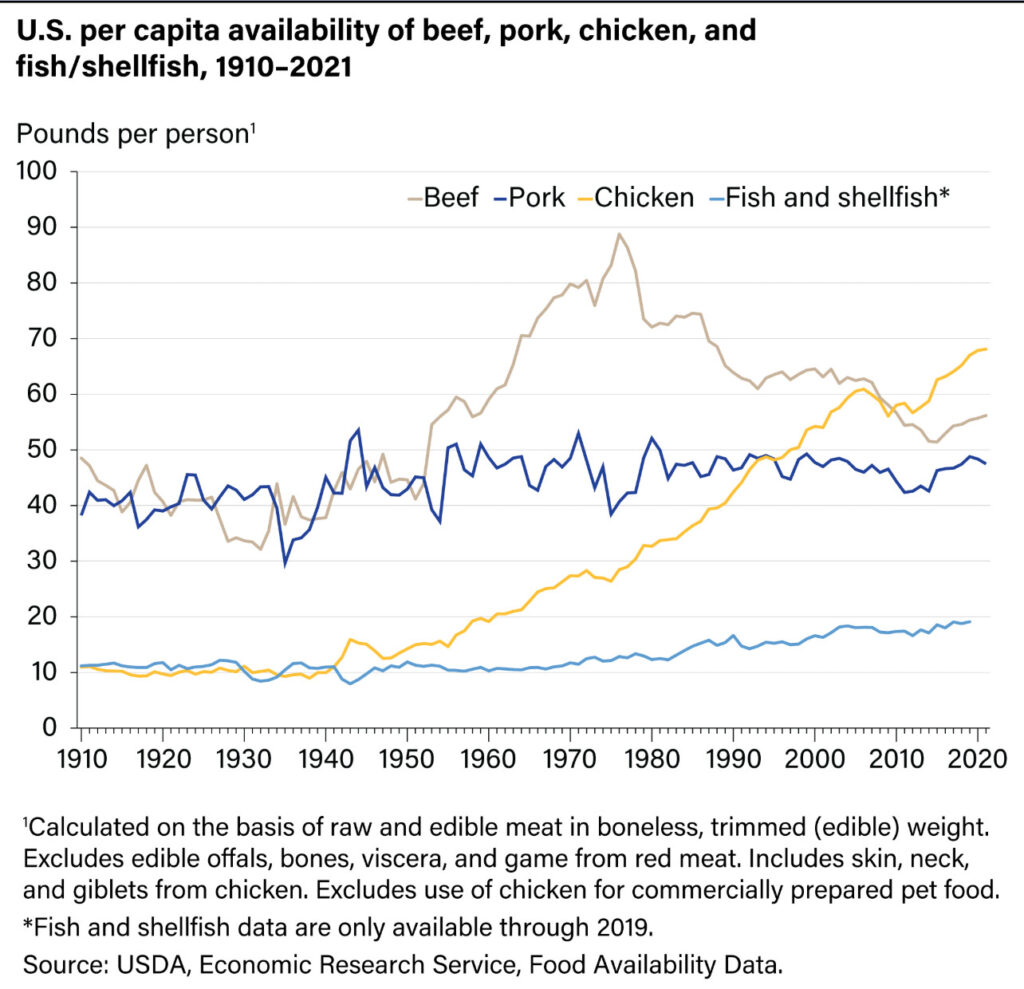

As chronic disabilities and diseases like obesity, type II diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (still the number one cause of death in the United States and many other industrialized nations) continue to rage at epidemic levels, Americans have continued to follow the official guidelines and recommendations by increasing poultry consumption. Since 2010, chicken has remained the most commonly consumed meat in the United States. According to the USDA, in 2021, the per capita availability of chicken for human consumption was 68.1 pounds, surpassing beef at 56.2 pounds and pork at 47.5 pounds. This trend has continued, with chicken remaining the most available meat for consumption in the U.S.

This week’s study from a group of Italian researchers questions those fundamental assumptions from the age of bellbottoms and platform shoes regarding one of the world’s most widely consumed meats.

- This prospective study collected data from almost 5000 (4869) middle-aged participants from southeastern Italy with an average follow-up of 19 years.

- The study group comprised approximately 52% males and 48% females.

- Dietary data were acquired from food frequency questionnaires.

- Weekly meat consumption was grouped into three categories, each divided into quintiles:

- Total Meat: less than 200 g, 201-300 g, 301-400 g, and greater than 400 g.

- Red Meat: less than 150 g, 150-250 g, 251-350 g, and greater than 350 g.

- Poultry: less than 100 g, 100-200 g, 201-300 g, and greater than 300 g.

- The Total Meat Group included lamb, pig, calf, horse, and beef under the category of red meat, and poultry and rabbit under the category of white meat.

- Those consuming greater than 300 g of poultry per week had a 27% increased risk of early mortality compared to those consuming less than 100 g.

- Specifically, for those consuming more than 300 g of poultry per week compared to those consuming less than 100 g per week, the risk of gastric carcinoma was more than doubled (227%), and was specifically higher in men (261%).

The Caveat:

Current dietary guidelines, recommendations, and expert consensus continue to recommend and promote poultry consumption, as opposed to red meat consumption, as the healthier option. It is also generally more affordable than red meat and is easily accessible, factors that no doubt contribute to the sustained adoption and adherence to this conventional wisdom. Current Italian healthy eating guidelines recommend 100 g of poultry 1 to 3 times a week and the most recent version of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) likewise recommends 26 ounces or almost 750 g (736 g) of poultry, meat, or eggs per week, with a preference for lean poultry options.[1]

Over the course of the study, 21% of the participants died from various causes, including gastrointestinal malignancies like gastric carcinoma (10.5%), liver cancer (3%), pancreatic cancer (2%), colorectal cancer (3.6%), and other cancers such as lung cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancer (17.5%). Other causes of death included myocardial infarction, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia. The mean age at the time of death was 81 (82.7 years for women and 79.9 years for men), and the mean age of the participants alive at the completion of the study was 65.4 years.

Interestingly, both moderate total meat consumption (200-300 g per week) and moderate red meat consumption (150-250 g per week) were associated with a statistically significant reduction of approximately 20% in the risk of early mortality. Higher levels of consumption, both in terms of total meat and red meat, were no different in terms of early mortality from any cause than the groups consuming the least amount of total meat (less than 200 g per week) or red meat (less than 150 g per week). In a direct rebuttal to the prevailing wisdom that consuming more poultry translates into a longer life, there was no similar benefit to moderate poultry consumption (between 100 and 300 g per week) in terms of a reduction in early mortality risk. In fact, as mentioned previously, the highest group of poultry consumers (greater than 300 g per week) had a statistically significant 27% increased risk of early mortality. Compared to the lowest group of poultry consumers (less than 100 g per week), all other quintiles of poultry consumers had a statistically significant increased risk of developing gastric carcinoma.

The takeaway here is not that poultry is worse than red meat or vice versa. In the centuries since King Henry sought a chicken in every subject’s pot as a measure of his kingdom’s prosperity, chicken has become less the once familiar yard bird and more of a CAFO (Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations) commodity. Critical to understanding the food-health relationship, particularly regarding individual ingredients or components like beef or chicken, is identifying both the method of production (how they are raised and processed, e.g., CAFO production and ultraprocessed nuggets) and the method of preparation (e.g., batter dipped and deep-fried). Both these critical pieces of information were lacking in this study. Unfortunately, this is quite a common finding, with it being estimated that only about 1% of the articles “identified in the scientific literature assessed the relations between poultry, processed poultry consumption, and human-health-related parameters.”

Understanding the complexities of the food-health relationship and identifying areas for intervention will require recalibrating the current investigative methods – which have resulted in recommendations that have epically failed us for more than half a century – to identify and assess the broader food-health ecosystem.

[1] (CREA, 2025; USDA, 2020)

The Study:

Additional Resources

U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

USDA. Food Availability and Consumption. USDA Economic Research Service. January 8, 2025. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/food-availability-and-consumption