In 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rolled out a major overhaul of the Nutrition Facts label, adding new science and clearer formatting to help consumers make healthier choices. The agency’s latest move—announced in late 2024 and early 2025— included two big changes: a mandatory front-of-package (FOP) nutrition label for levels of saturated fat, sodium, and added sugars, and an updated definition of the “healthy” label on foods. Together, these new guidelines build on the 2016 updates and further shift nutrition labeling toward simple, at-a-glance health cues. Experts say the goal is to tackle diet- related chronic diseases and improve health equity by making label information easier for everyone to use (FDA, 2025a; Todd, 2025).

The 2016 Nutrition Facts Revamp

In 2016, the FDA finalized a revision of the Nutrition Facts panel, the label on the back of food packages. The new 2025 design “reflect[s] updated scientific information, including the link between diet and chronic diseases” (FDA, 2023a). Key changes included a larger, bold calorie count and larger font sizes for better readability, a new line for “Added Sugars” (with a daily value percentage) and revised serving sizes to reflect the way people actually eat. The FDA also adjusted the daily values (DVs) percentage of nutrients based on the latest science and removed outdated information (e.g., “Calories from Fat” was eliminated).These updates were intended to present nutrition data more clearly, and the FDA noted that the changes would “help consumers make better informed food choices” by highlighting nutrients linked to diet-related diseases (FDA, 2023a). In practice, the 2025 label still lists a full panel of nutrients but uses bigger type and footnotes to make it less daunting.

How the FDA’s New Nutrition Labeling Rules Compare to 2016

| Figure 1 2016 Food Label. Source: FDA.gov | Figure 2 2025 Food Label. Source: FDA.gov |

Since the implementation of nutrition fact labelling in the 1970’s, studies and public health advocates have pointed out that many consumers struggle to interpret the detailed Nutrition Facts panel. Some analyses suggest that simply providing information isn’t enough if label design is confusing. For example, one policy analyst argues that nutrition disclosures are often “poorly designed” and “fail to actually inform consumers,” noting that labels sometimes do not account for how people perceive or interpret information (Abdukadirov, 2018). That critique has set the stage for the FDA’s more recent push: to simplify key data and meet consumers “where they shop.”

Front-of-Package Nutrition Labels

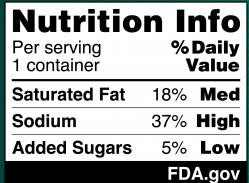

The big new proposal unveiled in January 2025 would introduce a mandatory front-of-

package (FOP) nutrition label on most packaged foods. This “Nutrition Info” box would be a stark departure from 2016’s purely back-panel focus. Under the proposed rule, packages would carry a small on-the-front summary showing saturated fat, sodium, and added sugars levels as “Low,” “Med,” or “High.” This proposed rule is still in the public comment phase and won’t begin review until after July 25, 2025. The FDA explains that these three nutrients were chosen because current dietary guidelines advise Americans to limit them for a nutrient-dense diet (FDA, 2025b). Importantly, this FOP label does not list calories; manufacturers could still choose to add calorie counts beside the box if they wish, but it is not required.

Figure 3 The new FOP (front of package) 2025 food label. These nutrients are categorized as “Low,” “Med,” or “High” to provide consumers with a quick snapshot of a food’s healthiness. Source: FDA.gov

The idea is to give shoppers a quick “at-a-glance” snapshot of a food’s healthiness while they are browsing, rather than forcing them to flip to the Nutrition Facts panel. As the FDA (2025b) notes, the front -of-package label is meant “to help consumers quickly and easily identify how foods can be part of a healthy diet.” The agency explicitly ties the move to prevention of chronic diseases. Diet-related illnesses (heart disease, diabetes, certain cancers) are the leading killers in the U.S., especially in under-served communities. By highlighting the nutrients most linked to those diseases, the FOP label is intended to steer consumers toward lower- sugar, lower-salt, and lower-saturated-fat options (FDA, 2025b).

Other countries have similar warning or traffic-light labels, and U.S. nutrition experts have long advocated something similar. The proposal represents a clear shift away from expecting consumers to decode a dense panel, toward providing a simple green/yellow/red–style cue on the front of every package. If adopted, the FOP box would complement the Nutrition Facts label— by retaining the full on the back of the package while making front-of-package marketing more factual and health-oriented.

Updated “Healthy” Claim Criteria

Meanwhile the FDA has also finalized a rule updating the definition of the voluntary “healthy” nutrient content claim on food packages. Under the old standard (based on 1990s nutrition science), many foods high in fat or sugar could carry a “healthy” stamp if they met loose thresholds. The new rule, which became effective in the of spring 2025, tightens those rules substantially. Now, to label a food “healthy,” the product must contain a meaningful amount of one of the USDA Dietary Guidelines food groups (fruits, vegetables, whole grains, dairy, or protein foods) and stay under strict limits for added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium (FDA, 2025c). In practice, this means that nutrient-dense foods like plain vegetables, fruits, beans, lean meats, and fat-free yogurt automatically qualify (since they are inherently low in sugars/salt/fats). But snacky or mixed foods must have enough whole grains, produce, or other healthy ingredients and keep sugar, salt, and sat fat low. For example, a whole- grain cereal could be “healthy” only if its sugar and sodium are modest.

The FDA says this change makes the “healthy” label consistent with modern dietary advice: by placing emphasis on healthy food patterns rather than the cutoff level for a single nutrient. The agency highlights that current guidelines stress getting enough foods from key groups and limiting added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium (FDA, 2025c). By linking the term “healthy” explicitly to those group-based patterns, the new rule aims to ensure that “healthy” foods are truly aligned with a nutritious eating style, not just low in one particular nutrient.

Why Change? The Push for Healthier Diets

The FDA’s new rules are driven by the sobering health toll of poor diets. In its announcements, the agency pointed out that American eating patterns fall far short of recommendations- most people eat far too few fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, while 63% of adults exceed the limit for added sugars and 77% exceed saturated fat limits (FDA, 2025a). These imbalances contribute to obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and certain cancers. As FDA official Rebecca Buckner put it, “We believe food should be a vehicle for wellness, not a contributor of chronic disease” (Todd, 2025).

Public health experts also note that low-income and minority communities suffer much higher rates of diet-related illness. The FDA explicitly frames the new rules as part of a broader strategy to make healthy choices easier and reduce health

inequities. Simplified labels could help these groups navigate food choices without needing nutrition training. In fact, the “healthy” claim revision and the proposed FOP label are both cited in the White House’s National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health, tying them to federal efforts to improve diet quality and food equity (White House, 2022). The 2016 Nutrition Facts update was also intended to incorporate the latest science on diet-chronic disease link and the current changes echo those goals. The difference is that the new changes target the consumer interface more aggressively. While 2016 merely refreshed the facts panel, the current rules try to proactively point out healthy vs. unhealthy foods at the point of purchase. It’s a move from detailed disclosure toward simplified guidance.

Implications for Consumers

The new labels are meant to boost shoppers’ health literacy and influence behavior. By seeing “High” or “Low” cues on fat/salt/sugar right on the front of the package, consumers may more easily compare products and judge which fits a healthy pattern. Early research suggests such front labels can nudge people toward healthier choices. A 2025 study by Y. Liu et al. found that adding a “healthy” symbol (using FDA’s proposed criteria) to yogurt packages changed how much people would pay. Interestingly, subjects were willing to pay 18 percent more for an unlabeled yogurt than for one labeled “healthy”. Liu interprets this as a sign that labels do influence perceptions—in this case, possibly making people worry that “healthy” product might taste worse. He cautioned that a simple health badge can “backfire if consumers are left wondering what qualifies the food as healthy.” The study also found that adding explanatory text (e.g., “meets FDA’s criteria: low in sat fat, sugar and sodium”) removed the pricing factor, indicating that clarity is crucial (Liu et al., 2025).

Implications for Manufacturers

Food companies must now consider both labels and formulations. Under the new “healthy” definition, many products that once could claim “healthy” will no longer qualify unless reformulated. Conversely, products reformulated to include more whole grains, vegetables or lean protein—while cutting sugar, salt, or unhealthy fats—could earn the coveted “healthy” label. For manufacturers, that could mean recipe adjustments: for example, a bread maker might increase whole grains and cut added sugar, or a frozen meal company might reduce sodium and add vegetables to hit the new targets. The FDA even notes that “if some manufacturers voluntarily reformulate food products to meet the updated criteria,” the overall food supply could improve (FDA, 2025c).

Industry Reactions

Food and beverage trade groups have been vocal on the subject. Some industry representatives have raised concerns about the science and cost of the new labels. For example, critics argue that mandating a one-size-fits-all box could penalize products unfairly or classify “Low/Med/High” may not fit all food categories. The Grocery Manufacturers Association (now the Consumer Brands Association) and others have questioned whether the added regulatory burden is justified and have urged the FDA to carefully consider implementation timelines (CSPI, 2025; Packaging Digest, 2025).

Public Health and Expert Perspectives

Nutrition scientists, dietitians, and health economists have largely supported the FDA’s

Moves, noting that the new rules are grounded in science and align with national dietary guidelines. For example, E.H. Belarmino et al. (2024) found that when the public defines “healthy” foods, they consistently emphasize fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and limiting sugar, sodium, and unhealthy fats—exactly the elements the updated FDA criteria focus on. Earlier work by Y. Fang et al. (2019) also demonstrated that revised labels influence food choices, especially among health-conscious

Looking Ahead: The Final Rule and Implementation

As of mid-2025, both the FOP nutrition label and the updated “healthy” claim are awaiting rollout, with the new back-of-package already finalized in April 2025. Implementation isn’t due to be completed until January 2028. (FDA, 2025d). This means that the earliest compliance for “healthy” claim updates is currently set to late April 2025.

References

Abdukadirov, S. (2018). Why the nutrition label fails to inform consumers. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3191319

Belarmino, E. H., et al. (2024). Consideration of nutrition and sustainability in public definitionsof “healthy” food: An analysis of submissions to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379567312

Center for Science in the Public Interest. (2025). The food industry’s false claims about front-of- package nutrition labeling: A fact sheet. https://www.cspinet.org/resource/food-industrys-false- claims-about-front-package-nutrition-labeling-fact-sheet

Fang, Y., Chen, Y., & Li, X. (2019). Effects of revised nutrition label design on consumer food choices. Journal of Consumer Policy, 42(3), 415–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-019- 09417-y

Food and Drug Administration. (2023a). Changes to the Nutrition Facts label. https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-food-labeling-and-critical-foods/changes-nutrition-facts-label

Food and Drug Administration. (2025a). FDA finalizes updated “healthy” nutrient content claim. https://www.fda.gov/food/hfp-constituent-updates/fda-finalizes-updated-healthy-nutrient- content-claim

Food and Drug Administration. (2025b). FDA issues proposed rule on front-of-package nutrition labeling. https://www.fda.gov/food/hfp-constituent-updates/fda-issues-proposed-rule-front- package-nutrition-labeling

Food and Drug Administration. (2025c). Use of the “healthy” claim on food labeling. https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-food-labeling-and-critical-foods/use-healthy-claim-food- labeling

Food and Drug Administration. (2025d). FDA extends the effective date for the “Healthy” final rule. https://www.fda.gov/food/hfp-constituent-updates/fda-finalizes-updated-healthy-nutrient- content-claim

Liu, Y., Jamieson, D., & Smith, K. (2025, February). Nutrition labels meant to promote healthy eating could discourage purchases. University of Florida News. https://news.ufl.edu/2025/02/nutrition-labels-study/

Packaging Digest. (2025, January). FDA advances front-of-pack food labeling rule—or tries to. Packaging Digest. https://www.packagingdigest.com/food-beverage/fda-advances-front-of-pack- food-labeling-rule-or-tries-to

Rowlands, J. C. (2006). FDA perspectives on health claims for food labels. Toxicological Sciences, 92(2), 295–299. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfl005

Todd, S. (2025, January 15). How the FDA’s new nutrition labels could prod the food industry to get healthier. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2025/01/15/nutrition-facts-label-fda-front-of- package-backed-by-science-opposed-by-industry/

White House. (2022). National strategy on hunger, nutrition, and health. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/White-House-National-Strategy-on- Hunger-Nutrition-and-Health.pdf